The Perfectionist Who Elevated the Yellow SubmarineAs seen in Beatlology Magazine, November 2008 Part of the 40th Anniversary Series on “Behind the Scenes of the Yellow Submarine” by Dr. Robert R. Hieronimus author of Inside the Yellow Submarine: The Making of the Beatles Animated Classic Why did the real Beatles hate the TV cartoon Beatles, but love the Yellow Submarine film Beatles? Why has Yellow Submarine been cited by multitudes of the big animators and designers today as a strong career influence? With 2008 marking the 40th anniversary of the theatrical premiere of Yellow Submarine (November 13, 1968 in the U.S.), we are taking the opportunity to remind you there were true identities with hearts and souls behind this film that we all love so well. One of them is the main reason this film is considered a classic today. Despite the fact that the same company, TVC of London, produced both the loathed TV series and the beloved film, they look so different because the director of the company, George Dunning, had a serious change of heart between the two productions. The TV series was kept simple in order to meet the weekly deadline for new animation, and it was produced simultaneously with hundreds of commercials, which were TVC’s mainstay. Before agreeing to produce a Beatles feature film, however, Dunning stuck in his heels with the producers from King Features, and determined to create a lasting work of art. Remembered as both a legend and a genius in the field of animation, George Dunning is also character of contradictions. He was brilliant but indecisive, mostly aloof yet fiercely loyal, demanding perfection while remaining unavailable. Key Animator Cam Ford recalls: “To most animators working on Yellow Submarine, George Dunning was almost ‘the man who wasn’t there.’ We saw very little of him during production, as he tended to work from the Dean Street studio and liaise mainly with sequence directors Bob Balser and Jack Stokes, who would then pass his ideas on to us. He did not socialize with us much either, only very occasionally turning up at the Dog and Duck pub for a quick drink. He was a very pleasant chap, but extremely quiet, and his reply to any question was inclined to be slow, monosyllabic, and noncommittal. Getting him to make an actual decision, according to Jack Stokes, was like pulling teeth. “A typical example of this was the day he came into our room to use the studio’s Lucidograph (a camera-like device that enabled animators to enlarge or reduce their drawings) - naturally called ‘Lucy’ by everybody - which stood in one corner. George switched on the Lucy, placed a drawing on the artwork board, then climbed up on the step and vanished behind the machine. He twiddled the wheels a little – and then nothing further happened. Some time later, one of the animators said, ‘Is everything okay, George?’ and, after a pause, he quietly replied, ‘Um…I don’t seem to have a pencil.’ “‘No problem,’ said the animator. ‘Borrow one of mine. What would you like? HB? 2H? F? 2B?’ The sudden stress of having to make an instant decision flustered George completely; he ‘umm-ed and ahh-ed’ for several minutes, then picked up his drawing and left the room, muttering something about it ‘not being important.’” Ford’s memory is echoed by others involved in the film, like Norman Kauffman, the general production assistant on the film, who said Dunning seemed to always take a few minutes before answering you. “He took everything in,” said Kauffman, and had a “very slow Canadian way of talking.” Everyone agreed, however, that George Dunning elevated Yellow Submarine to a work of art. He was such a fine artist and innovator himself, he set the tone for everyone on the crew to strive for perfection, even though they had less time and less organization than normally expected on an animated feature. Assistant Dubbing Editor Antal Kovacs remembered Dunning’s perfectionism and wondered what would have resulted had their schedule not been so compressed. “He would go to the rushes and very often, he would just say, ‘I don’t like it. Do it again.’ George was very, very painstaking – a perfectionist. There was an incredible element of time against money, and George, I think, suffered very badly. Had he been given the time he needed to do it properly, and the means to do the film properly, it could have been an even better film.” It would have been a very different film, that’s for sure. Dunning’s signature style is seen in the “Lucy in the Sky” sequence, and you can imagine the impact if the whole film had been created in that floaty, ethereal, boundary-less style. Though the “Lucy” sequence is a fan favorite, it would have literally taken several years to produce a feature length film in that style. Out of necessity, they needed a designer with a more restricted and precise style, and fortunately, they found Czech-born graphic designer Heinz Edelmann whose limitless imagination and satirical whimsy created the worlds of Pepperland and the challenging Seas between it and Liverpool. Edelmann’s complete immersion in the Yellow Submarine and Dunning’s obsession with “Lucy” are both examined in depth in Inside the Yellow Submarine, but it was not until after that book saw publication that we discovered Cam and Diana Ford, now living in Australia. Diana was one of the lucky few assigned to the “Lucy” sequence as a rotoscoper, tracer and painter, and in a subsequent interview that has never before been published we asked her to share her memories of working in this slightly isolated department. She recalled George Dunning as “a bit of a mystery to most of us girls. He was a shadowy figure who appeared and told us to do certain things and then vanished.” They saw a great deal more of animator Billy Sewell upon whose original unfinished film “Half In Love with Fred Astaire” the “Lucy” sequence was built. The Fords estimate that about one third of the “Lucy” sequence was from Sewell’s original piece, but as Diana admitted, they did an enormous amount of work that was never used, and it was difficult to tell what originated where. Diana spent weeks on the rotoscope, a projection machine that allows the artist to trace over actual film footage frame by frame on to cel (celluloid), after which the outlines are painted in by hand – one of the oldest methods of animation known. Bill Sewell was mainly the one who selected and assigned the old movie footage to be used. He had been working on this sequence independently that wasn’t even linked to the Yellow Submarine at first, but everyone who was anyone in animation had been persuaded to join this crew, and somehow Dunning convinced Sewell to let him incorporate his unfinished Fred Astaire movies into the Submarine. They gave the trace and paint girls in the “Lucy” department a great amount of freedom to decide how to paint over the rotoscoped images and what they did with their fingers. Diana says that no one really told them how or what colors or approaches to use. “That was the effect of Lucy,” she said. “They wanted something which was free-wheeling and something which was mad. It’s a total antithesis to the rest the film because it’s as free as the rest of it was constrictive. “But ‘Lucy’ was wonderful. You could flash around with paint and loo [toilet] paper, eat a piece of cheese and then put your fingers on the cel and swirl it around and nobody seemed to mind. We were astonished when it worked.” Unit Director Bob Balser picked up this sequence when Billy Sewell returned to Canada for another job, and Balser estimated that when he got there he found over a half hour of footage to illustrate a song was just over three minutes. It took all of Balser’s skill and patience to select the right footage to match up to the tempo and the lyrics of the song and also to interweave other images from the rest of the film for the sake of continuity. Like almost everyone else on the crew, Bob Balser cannot speak highly enough of George Dunning, calling him a “very profound thinker and a marvelous designer,” and one of the great geniuses of animation. From his beginnings at the National Film Board of Canada, working under the inspired supervision of Norman McLaren, Dunning went on to produce some of the funniest and most revolutionary and award winning cartoon films. It could be argued that the majority of the output on Yellow Submarine might more appropriately be attributed to Dunning’s two unit directors on the film (Jack Stokes and Bob Balser), and it also might be true that more of the innovative styles and techniques seen throughout the film came from others like Charlie Jenkins and Heinz Edelmann. But there is no question that the Yellow Submarine would have been a 90-minute slapstick starring the Saturday morning TV cartoon Beatles if it were not for the quiet determination of George Dunning. Inside the Yellow Submarine is available at amazon.com. Autographed copies and related items can be purchased from http://www.21stCenturyRadio.com/yellowsub, where you will also find the other 40th anniversary articles in this series. This article was prepared with the assistance of Jodi Brandon and Laura Cortner. |

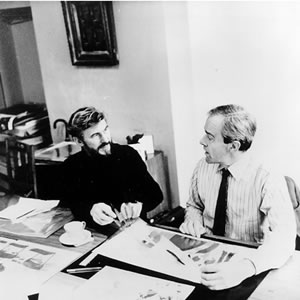

Unit director Jack Stokes and his TVC partner George Dunning, overall director on Yellow Submarine. Stokes remembered that getting Dunning to make decisions was like pulling teeth.

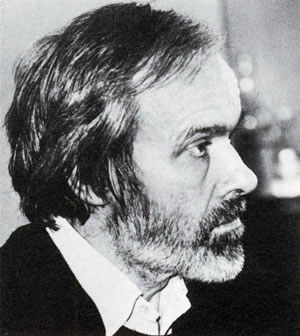

George Dunning’s health was failing as he worked on Yellow Submarine, and the stress of the short deadline and lack of script actually hospitalized him for a considerable portion of the production.

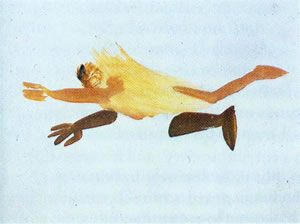

Dunning’s award-winning “Flying Man” (1962) show a pre-‘Lucy’ attempt at expressing fluid motion through brush strokes and his desire to avoid the common use of the outline to define shape.

The stubbornness of George Dunning is credited for elevating the quality of the artwork on Yellow Submarine even though it was also his TVC London company that produced the much more simplistic Beatles TV cartoon series earlier.

Diana Ford was one of the rotoscoper/tracer and painters on the “Lucy in the Sky” sequence. She remembers long hours of tracing off seeming unrelated frames of films from the 1930s.

“You could flash around with paint and loo [toilet] paper, eat a piece of cheese and then put your fingers on the cel and swirl it around, and nobody seemed to mind,” remembers Diana Ford of her work on the “Lucy in the Sky” sequence. |